Five Determinants of Digital Poverty

Digital poverty is the inability to interact with the online world fully, when, where and how an individual needs to. We skimmed the surface of the topic in previous blog post; in this post, we will take a deeper dive into the five key intersecting areas which determine whether or not a person is digitally impoverished, and to what degree.

The five determinants are: devices and connectivity, access, capability, motivation, and support and participation.

Devices and Connectivity

A digital-first society is one which adopts the mindset that a digital solution should be employed whenever there is the potential to do so. For example, offering patients an online appointment with a GP instead of them visiting the practice in person. The UK Government began the rollout of their digital transformation agenda in 2010, since which the nation has become increasingly digital-first, making internet connectivity and device access a necessity rather than a luxury.

It is no longer just a case of a household being either on- or offline, there are degrees of access which are affected by factors such as speed and cost. The digital landscape is at least partially dictated by what economists call a “planned obsolescence of hardware and software”. What this means is that manufacturing companies purposely build their products to breakdown so that you have to buy a newer, more expensive product to replace it. So a household could be online in that it has devices which connect to the internet and the users have the necessary skills to access it in a certain way, but they can still experience digital poverty if they have outdated hardware or lack the skills to use new software with a degree of confidence.

Speed

A 10 Mbps (10 megabits per second) connection speed pre-pandemic would have been sufficient for a household to access emails and load most static websites. But you need a much faster (ergo, more expensive) connection to be able to livestream a video conference, which has become increasingly necessary as people have moved to working and learning from home. If you consider that a household could include two working adults and one or more child, all of whom need sufficient connectivity to stream simultaneously, it becomes apparent that a faster connection speed is not just a luxury for being able to stream movies more smoothly.

In 2020 the government set up the Universal Service Obligation for broadband, which determines that a 10 Mbps download/1 Mbps upload speed should be a basic standard and allows households to request a better connection if their supply does not meet these minimums.

Cost

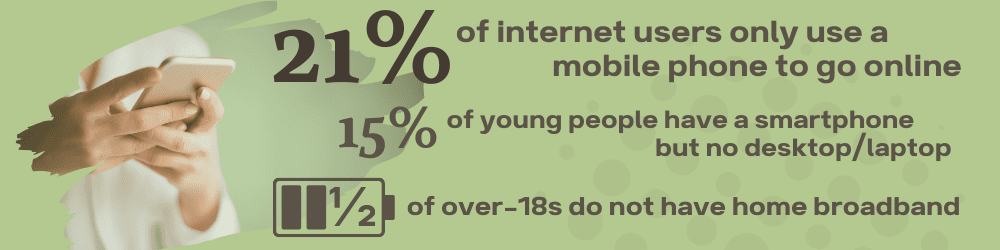

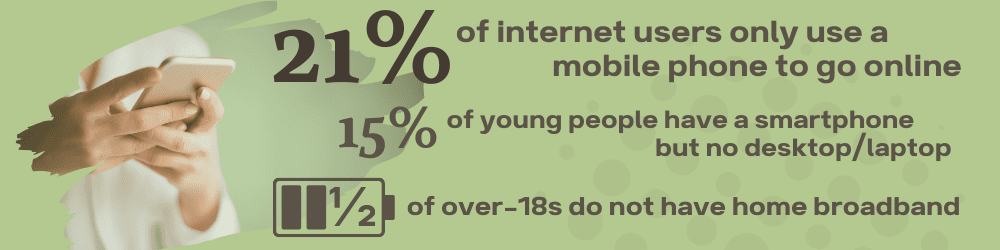

National surveys show that poorer people typically rely on mobile phones for connectivity to the internet. Mobile data prices are consistently higher than fixed line prices, meaning that the poorest users are often paying more for a connection with comparatively limited service, as 55% of such people have reported that completing online forms or editing documents is significantly more difficult on a smartphone than on a desktop or laptop. And the longer you are online, the more data you use.National surveys show that poorer people typically rely on mobile phones for connectivity to the internet. Mobile data prices are consistently higher than fixed line prices, meaning that the poorest users are often paying more for a connection with comparatively limited service, as 55% of such people have reported that completing online forms or editing documents is significantly more difficult on a smartphone than on a desktop or laptop. And the longer you are online, the more data you use.

Data poverty has come to exist as a concept, meaning the inability to afford sufficient, private, and secure mobile or broadband data.

Number and Type of Devices

Having access to a variety of devices enables a person to tailor their use of the internet according to the device. For example, you would struggle to write a school essay on a mobile phone; a laptop/desktop would be much more convenient. Research shows that the number of devices an individual has access to, the stronger their digital literacy.

Access

Digital technologies have the potential to impact the lives of disabled people in particular to an incredible degree. For example, smart speakers can bring a higher degree of daily independence to the lives of individuals who are visually impaired or afflicted with physical limitations. In spite of this potential, though, disabled adults make up a disproportionately large segment of adult internet non-users, often citing lower levels of confidence and skill in navigating the digital world. Two key areas that perpetuate this exclusion are digital design and cost.

One aspect of digital design that has repeatedly been called out for unfairly discriminating against disabled users is the reCAPTCHA element, the web feature which requires users to input a string of text or click on a photograph collage to prove they are not a bot. The strings of text are intentionally difficult to read, which prevents human users with certain visual and learning impairments from being able to prove they are in fact human, and the prompts often time-out too quickly to accommodate users who struggle to type or click quickly enough.

Assistive technologies do exist to help differently-abled individuals to access the digital world, but they can be prohibitively expensive to purchase and implement, making cost a significant barrier to accessibility and therefore a determinant of digital poverty.

Privacy and Space

Social restrictions during the pandemic severely isolated individuals who formerly relied on public libraries or cafes/restaurants offering free Wifi, underlining how social spaces, or rather the lack thereof, can significantly contribute to digital exclusion. Those who felt this impact the hardest were people already suffering from digital poverty, in particular older people and those from low-income households.

Privacy whilst using digital technology is of paramount importance when you consider that a number of services, such as court tribunals, GP appointments and mental health support sessions, are increasingly being offered online. An individual cannot be expected to discuss intimate aspects of their private life in a public setting. Similarly, public WiFi connections are less secure and more vulnerable to security attacks, meaning that those who have to use public internet access for online banking or for completing application forms requiring personal data, such as benefit or immigration applications, are at a disproportionately higher risk.

Safety

Accessibility is not purely about the physical ability to access the digital world, it also incorporates the willingness to do so. Having negative online experiences can greatly impact an individual’s motivation to continue to participate online. Identity theft, cyberbullying/trolling, scams, misinformation and data breaches have all been identified as common concerns affecting a person’s willingness to access the digital world, and they tend to be disproportionately experienced by social groups who already bear a diminished representation online: those living with disabilities and those from low-income households.

And so, lacking access to a private, secure space in which to conduct online actions can be a barrier to digital inclusion and a determinant of digital poverty.

Capability

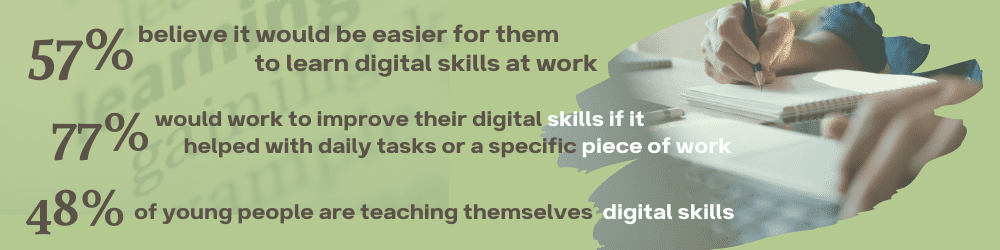

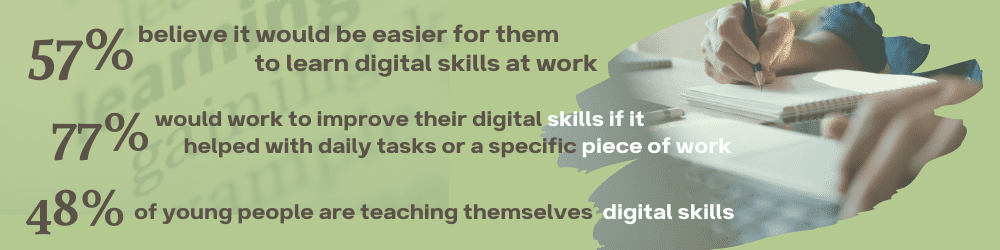

The UK Digital Poverty Evidence Review 2022 states that “technologies do not exist in a vacuum… people need to be supported with skills in order to benefit from digitisation”. It is estimated that only between 20% and 50% of the UK population possess the necessary digital skills needed to live a comfortable digital life.

Digital Skills in Context

Reports conducted on homeschooling during the pandemic discovered that a child’s capability to learn the necessary digital skills to be able to learn in a remote classroom environment were heavily influenced by the comparative skills of their caregivers. Affluence has a sizeable sway over the likelihood of an individual to be interested in, motivated to acquire, and able to apply a digital skillset. Those who were raised in high socio-economical households were found to be presented with more opportunity and encouragement towards the exploration and pursuit of mastering digital literacy. Whereas conversely, those raised in low-income households were often actively discouraged from engagement with digital technologies, largely due to the associated cost. This way of thinking has coloured the opinions of many digitally disadvantaged children that tech careers are “not for people like [them]”.

Device-Limited Literacy

As highlighted in the Access section, the number and type of devices an individual has access to can greatly affect their degree of digital literacy. It is not just the quantity of the engagement that needs to be considered, but also the quality of it. Social media plays a large role in this discourse; it is as much a staple of the online activities of highly literate, extensive internet users, as it is to those of much more limited users. Indeed, there are internet users who largely curtail their consumption of digital technology to social media streams.

Ofcom has defined a category of narrow users: those who participate in between just one and 10 of the activities set out in its surveys. People who access the internet solely through a smartphone tend to fall into this category – a growing rank of internet users who can both struggle to perform certain fundamental tasks online, whilst deftly navigating the majority of web content, preferring to access the online world via their mobile rather than a desktop, laptop or tablet. This new concept of device-limited literacy, having proficiency with one type of device but lacking it with others, most often applies to younger people who have grown up using and are familiar with newer technology such as smartphones, but are unskilled with a mouse and keyboard. It can be an error to assume that somebody is a digital native purely because they spend a lot of time on the internet. A true native is somebody who has a broader knowledge of different hardware and software, of different operating systems and platforms.

Data Literacy

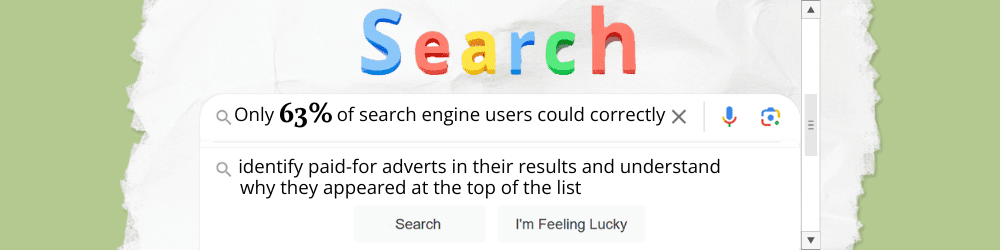

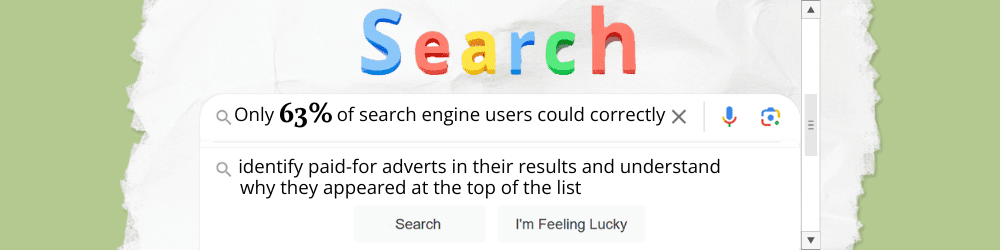

Data literacy is the concept of being able to understand and make choices about how one behaves in the digital world; being aware of how and why different public and private entities collect, store and use data about individuals to provide services, including advertising, so as not to generate a response of fear.

Motivation

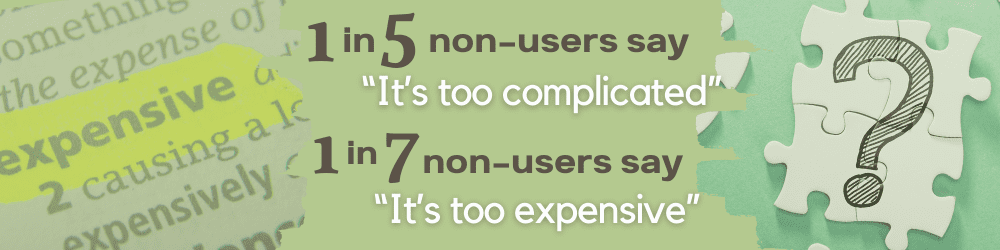

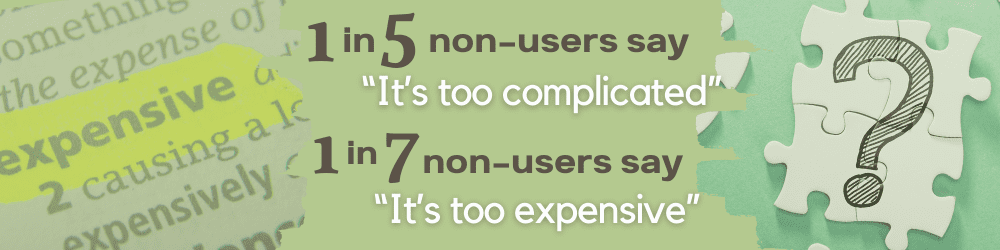

Necessity does not automatically translate into motivation. Many people are hesitant to get online and acquire a set of digital skills, and it is mostly thought to be due to cost, privacy concerns and their life-stage. Whilst it is important to allow people who want to get online to do so, it is also important to respect the decision of people who have made an informed choice to stay offline, and they should be provided with alternatives to a digital-first society.

Inclusive Design

Research has shown that platforms often employ dark patterns, a technical nudge to trick users into making choices that might harm them, like being forced to accept a list of terms and conditions consenting to share more data than they realise before they can use a product. These tactics are actually design choices on the part of the developers, and they are having an adverse effect on the motivation of people to participate in the digital world. Technology developers should be held to account and forced to make better, more inclusive design choices in designing their products. Products designed in partnership with intended users often give the user a greater sense of agency and empowerment, thereby motivating them to continue to use the product.

Research needs to consider that when somebody says they are not interested in the internet because it is too expensive, they might mean that any cost would be too expensive (perhaps they are unemployed and rely on Universal Credit), or they might mean that costs should be lower for lower speeds (they think companies charge too much for slower packages and would be interested if prices were lowered). It is important to be able to differentiate between non-users who have made an informed choice not to engage in the digital world, and those who are actually digital excluded.

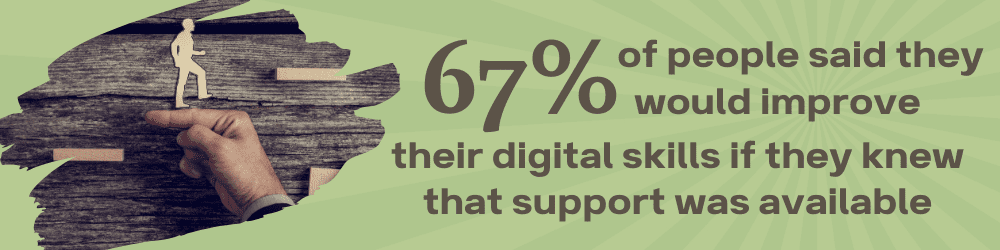

Support and Participation

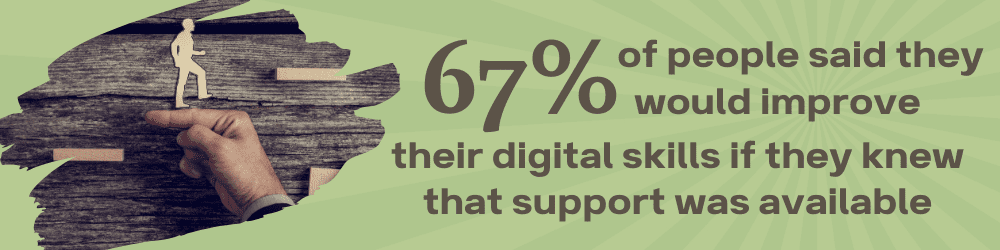

Research repeatedly indicates that a large percentage of non-users would be more inclined to get online and improve their digital skillset if they knew where and how to get the right support for them. Digital inclusion sector charities (like Sovereign House GH), with additional initiative from the UK Government, local councils, and industry, are providing a wealth of courses, both on- and offline.

Here are just a few examples:

- Sovereign House GH: click here for more information about the digital skills courses we offer, both to children and those aged over 50, at our Bury learning centre

- Good Things Foundation: www.goodthingsfoundation.org – have over 2,000 online centres

- Citizens Online: www.citizensonline.org.uk – run courses to train digital champions

- AbilityNet: www.abilitynet.org.uk – offer specialist one-to-one support for disabled people

But not everybody knows that this support exists, or the ones they know about are not suitable for their lifestyle or needs. This is a “crucial bridge out of digital poverty”. People learn best through trusted networks they are already a part of.

Informal Networks

Whilst formal pathways towards learning, such as online courses, may work for some people, there is increasing research to show that informal learning might be more appropriate for certain individuals who have had a bad experience of formal education and are less likely to want or even know how to access support. These people would learn most effectively if they were taught through informal pathways.

A lot of non-users are already getting friends and relatives to complete certain tasks online for them, these helpers are known as proxy users. Proxy users have a role to play in helping to teach the people they are helping so that they can do it for themselves instead of staying digitally excluded. Learning from somebody you know in a familiar environment boosts your confidence and makes you feel more comfortable, meaning that you become more comfortable with your online participation too. The digital champion model is based on this logic, where anybody with a set of digital skills has the ability to help teach somebody else that they know. This is a key to preventing digital poverty.

Conclusion

Learning digital skills is not about completing a course and then you are qualified for life, learning is an ongoing process and there is a danger of people getting left behind if they do not remain interested in the process. Too many strategies for overcoming digital poverty treat inclusion as being like a ladder that you can progress up, without accounting for a multitude of factors that can get in the way or cause people to take a detour in their learning, such as illness, childcare responsibilities, unemployment, financial hardship, and many more.

Ultimately, the factors that are determinants of digital poverty will affect all of us at some point in our lives, and we will all go through peaks and troughs in regards to our access, capability and motivation to learn, adapt and integrate ourselves into the digital world. The important thing is that support is available, and known about, for people at each step of their journey in a way that suits their individual needs.